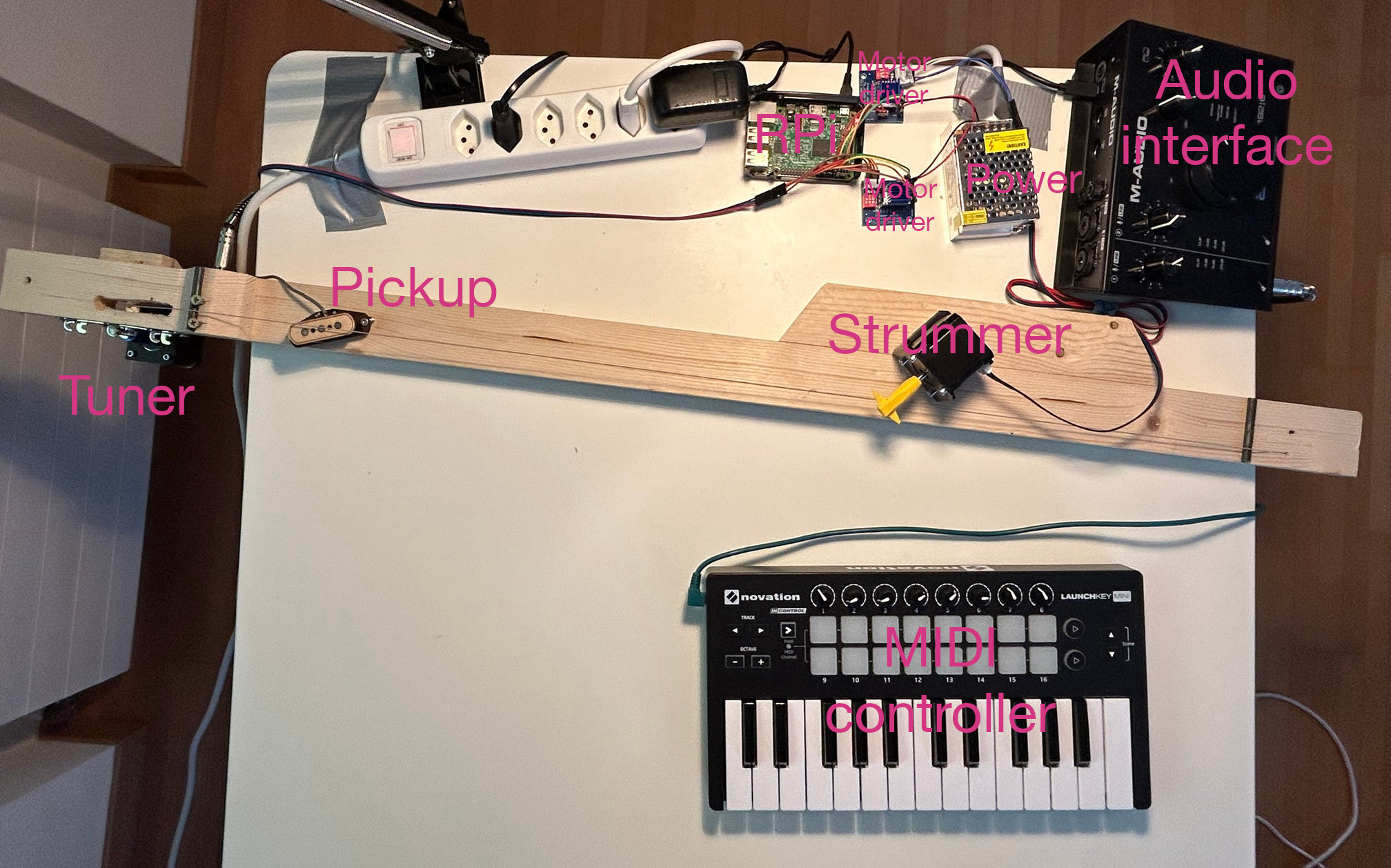

Autoguitar

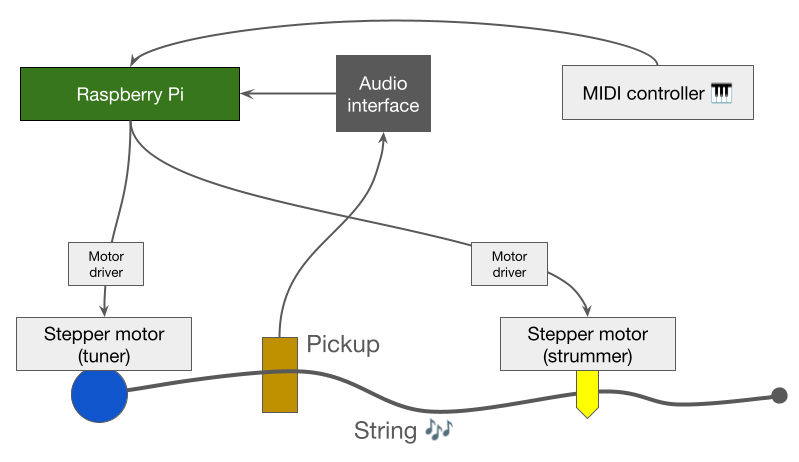

A robotic stringed instrument: one motor tunes the string, and another one plucks it. Fretless, since the pitch is controlled by tuning. Controllable via MIDI.

I decided to make this because I have plenty of experience with making software, but hardware is completely unfamiliar territory for me: my first step in this project was to google what voltage is.

Shoutouts to Elio Fistarol who helped me massively with the hardware aspect and showed me a dozen of different machines for cutting particular things in particular ways. And shoutouts to the ETH Student Project House whose Makerspace gave me access to said machines.

Here is a demo of the guitar in action. At the moment, it’s just one string, but you could extend this to several strings to be able to play chords. Let’s take a closer look at how it works:

Or, in diagram form:

Here is what happens when you press a key on the MIDI controller:

- The Raspberry Pi deceives a signal saying that a key was pressed.

- It turns the strummer motor to pluck the string. In the demo video linked above, I’m using a tremolo mode where the guitar is automatically strummed all the time, but let’s imagine that’s off.

- Simultaneously, it turns the tuner motor to tune the string to the note that you pressed on the MIDI controller.

- It continually gets audio from the pickup and computes the current pitch of the string.

- If the pitch is lower than it’s supposed to be, it winds the string up to increase the pitch, and vice versa.

Hardware

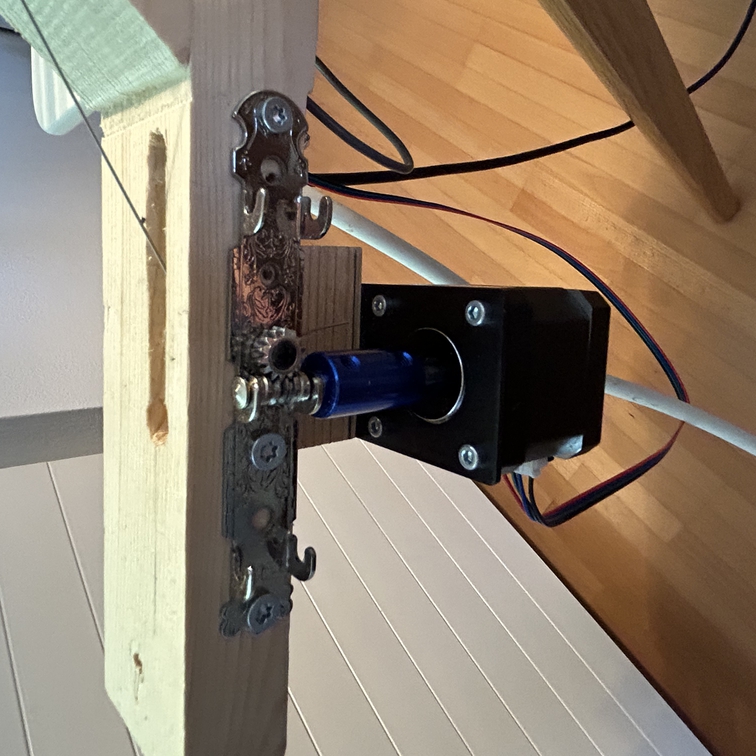

Both the tuner and the strummer use NEMA 17 Stepper motors. The tuner motor is connected using a coupling to a repurposed classical guitar tuning peg on which the string is wound.

I also tried winding the string directly onto the stepper motor’s axis, but then the motor needs a much higher torque to wind the string.

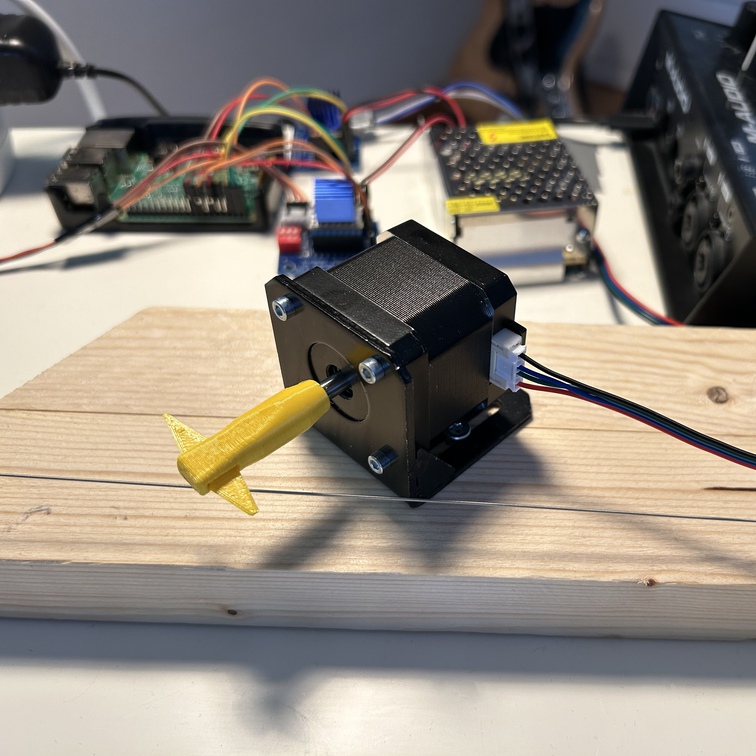

The strummer motor is directly attached to a 3D-printed strummer that Elio designed. The diamond-shaped pick is detachable from the holder so that it can be easily exchanged. That proved to be handy because I’ve already broken a few picks – the resin is not as tough as the regular picks’ plastic.

Fancy model-based tuning

The tuning strategy described above is a simple proportional controller: in each time-step, I turn the motor by a number of steps that’s proportional to the difference between the target and actual frequencies.

But this has disadvantages: pitch detection is computationally expensive for the poor Raspberry Pi and you need to take a fairly large chunk of audio (~100 ms) for the measurements to be stable. This leads to a slow feedback loop, meaning delays and overshooting.

An alternative is to use a model-based approach: we know the physics of strings, so if we receive an instruction like “go from 150 Hz to 200 Hz”, we could compute precisely how much to turn the motor to get to that frequency, without having to use the feedback loop.

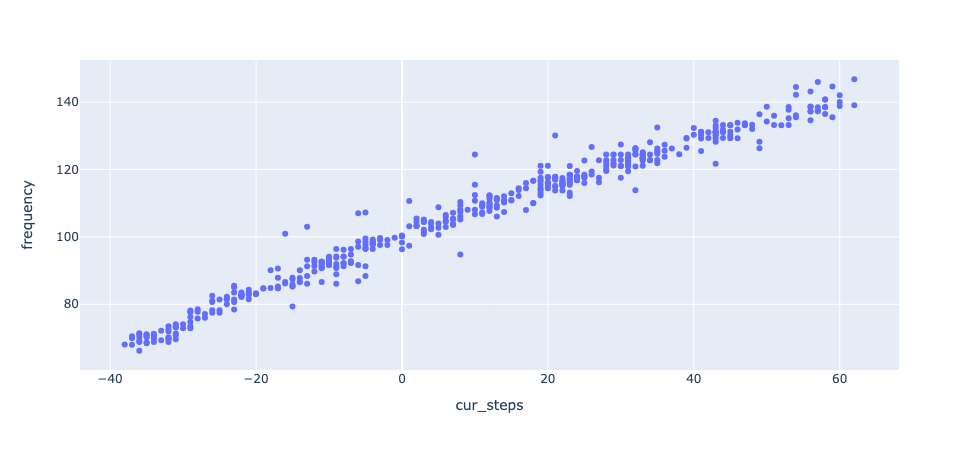

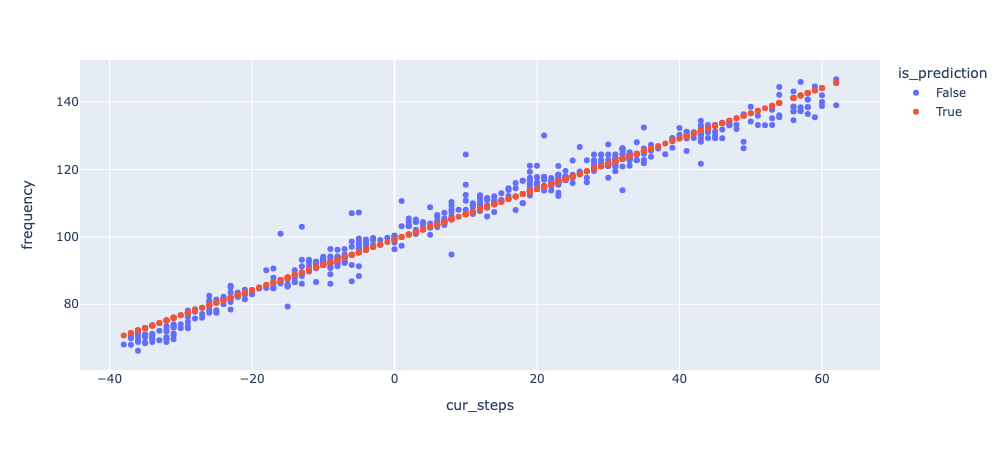

Here is a plot of the string’s frequency as a function of how many steps the motor has been turned, relative to an arbitrary zero-point.

Looks like a simple linear relationship. This is what we get when we fit a linear regression model to the data:

Not bad, but you can see how the estimatated frequency is too low on the sides, and too high in the center. And that’s not due to noise: linear regression is actually not the correct model!

That’s because according to physics, the frequency of the string is actually proportional to the square root of the stretching force, and our model assumes it’s proportional to the force itself (=the number of steps the motor was turned).

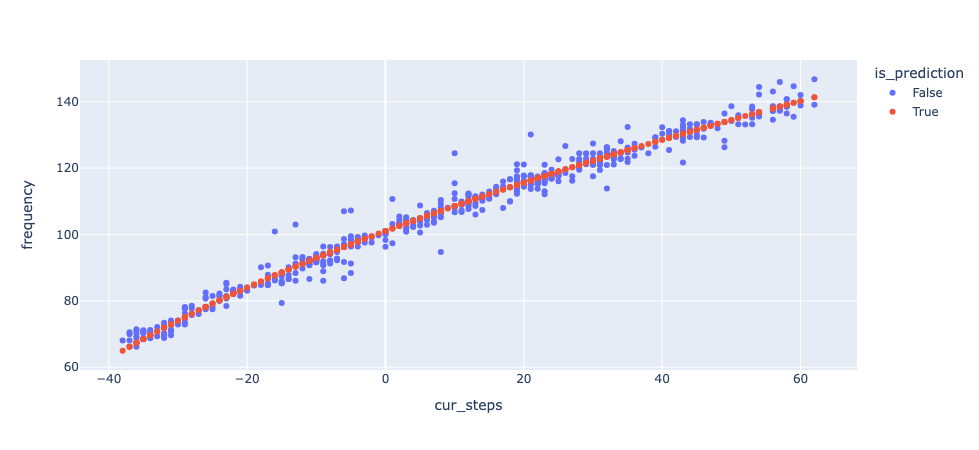

We can still model this using linear regression. Our original linear model is \(f = as + b\), where \(f\) is the frequency, \(s\) is the number of steps and \(a\) and \(b\) are the parameters we fit to the data.

Now we want \(f\) to be a function of \(\sqrt{s}\), which makes the model non-linear in \(s\). But what we can do is instead take the square and predict \(f^2\) as a function of \(s\). We can then simply take the square root of the prediction to get \(f\). This is the fit we get:

Much better! We can now use this model for tuning. By inverting the model we get a function from frequencies \(f\) to motor positions \(\hat{s}(f)\). Essentially, this means “if you want to get frequency \(f\), you should turn the motor to \(\hat{s}(f)\)”. So now when we press a key on the MIDI controller, we can just look up \(\hat{s}(f)\)” and turn the motor to that rotation.

Notice that since there is no feedback loop any more, we no longer need the pickup! We only need it at startup, because we don’t know what frequency the guitar started at – or, equivalently, what is the initial rotation of the motor.

What’s next?

This is the state of the guitar in July 2024. It already works well, but there are still some issues:

Slow tuning

The tuning motor is rather slow: tuning by an octave takes maybe 500 ms. The solution is clear – use a stronger motor. That, however, does have the disadvantage of increasing the risk of popping the string accidentally. The current motor is not strong enough to pop the string by sheer force, so even if I introduce a bug, the consequences aren’t that bad. With a stronger motor, I’d likely go through many more strings.

Frequency range

The range is only about one octave, because then the strings start popping. And if we tune the strings much lower than they’re meant to be, they sound bad.

This could be solved by having multiple strings in parallel. After all, this is how the issue is solved in a regular guitar. Being able to tune a string one octave up corresponds to having 12 frets on a string, so the single-string range is actually not too bad.

Hardware slack

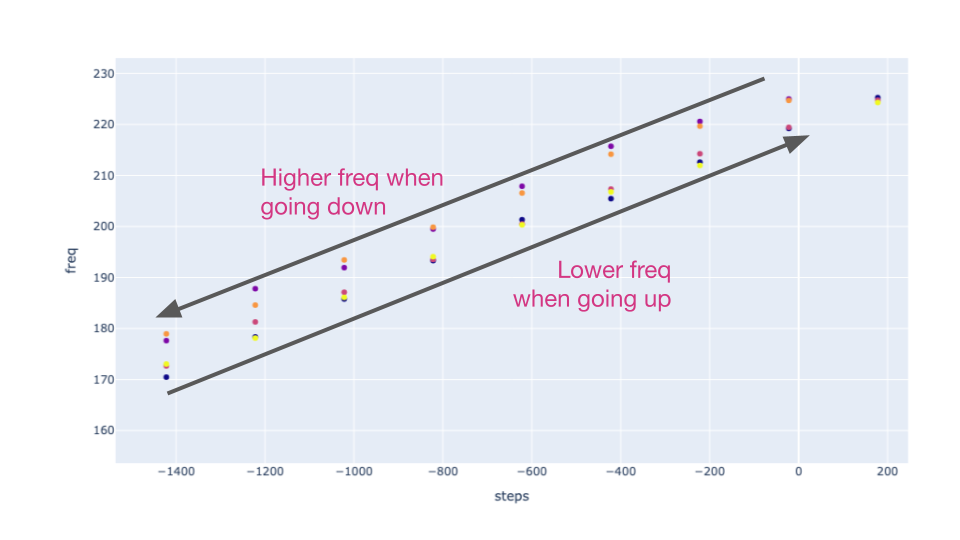

After implementing model-based tuning, I noticed the guitar sounds out-of-tune. I thought this might be an issue with how I’m fitting the data, but when I measured carefully, I discovered this pattern:

I had the guitar play a scale up and then back down, and noticed that the data is very consistent when the scale is being played in the same direction, but there is a clear difference between the two directions! Namely, when the scale is going up – meaning we’re winding the string up – the frequency is lower than if we reach the same motor position when we’re going down!

This is due to some hardware slack. The string likely has some kind of “momentum” due to the friction coming from the bends on the two sides. That means it doesn’t fully go to the “ideal frequency” that should be reached according to physics, and the offset depends on what the previous frequency was.

Computational power

One of the bottlenecks is that pitch detection is comptuationally expensive for the Raspberry Pi. If I had more accurate and lower-latency pitch detection, I could hopefully go back to the proportional controller and discard the fancy model-based tuning.

This would solve the hardware slack issue because then we wouldn’t rely on the model being accurate – the proportional controller would get it to the correct frequency, no matter what.

I realized this is not too difficult to solve: simply offload all computation onto my laptop, which is orders of magnitude more powerful. The Raspberry Pi would only be used as a dumb controller that receives instructions from the laptop. We can do this by running a simple server on the Pi that we can send commands to, like “turn the motor by 50 steps”. To receive the input from the audio interface and the MIDI keyboard, simply connect them to the laptop instead of the Pi.

On my WiFi, this introduces about 10ms of latency. It could likely be lower if I used an ethernet cable to connect the Pi with the laptop. For real-time musical applications, the lower latency the better, but as a rule of thumb, below 50 ms is acceptable, so this is ok.